Sinking of the USS Indianapolis

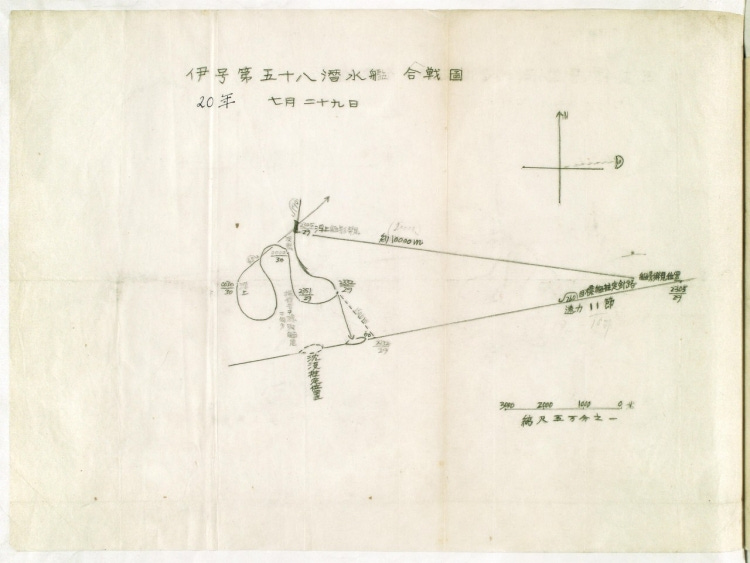

Shortly after midnight on July 30, 1945, one of the most horrific episodes in a six-year war began to unfold in the Pacific. A pair of torpedoes fired by the Japanese submarine I-58 slammed into the heavy cruiser Indianapolis, sinking her within 15 minutes and initiating a hellish four-day ordeal for the survivors.

Of the 1,196 men aboard that evening on a voyage from Guam to Leyte, only 316 would survive. The 880 dead from the Indianapolis bookended the loss of 1,177 men aboard the USS Arizona on December 7, 1941 as the U.S. Navy's most costly tragedies of the war.

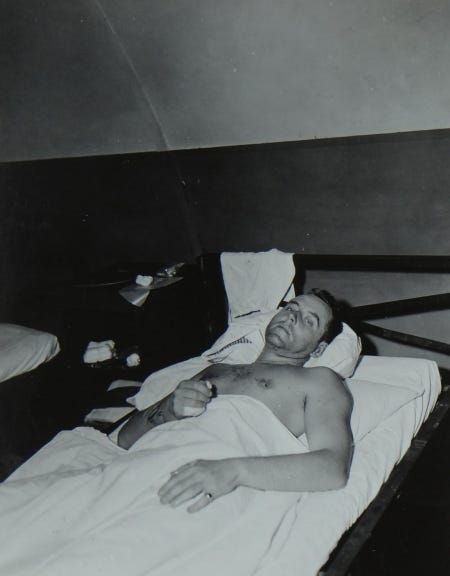

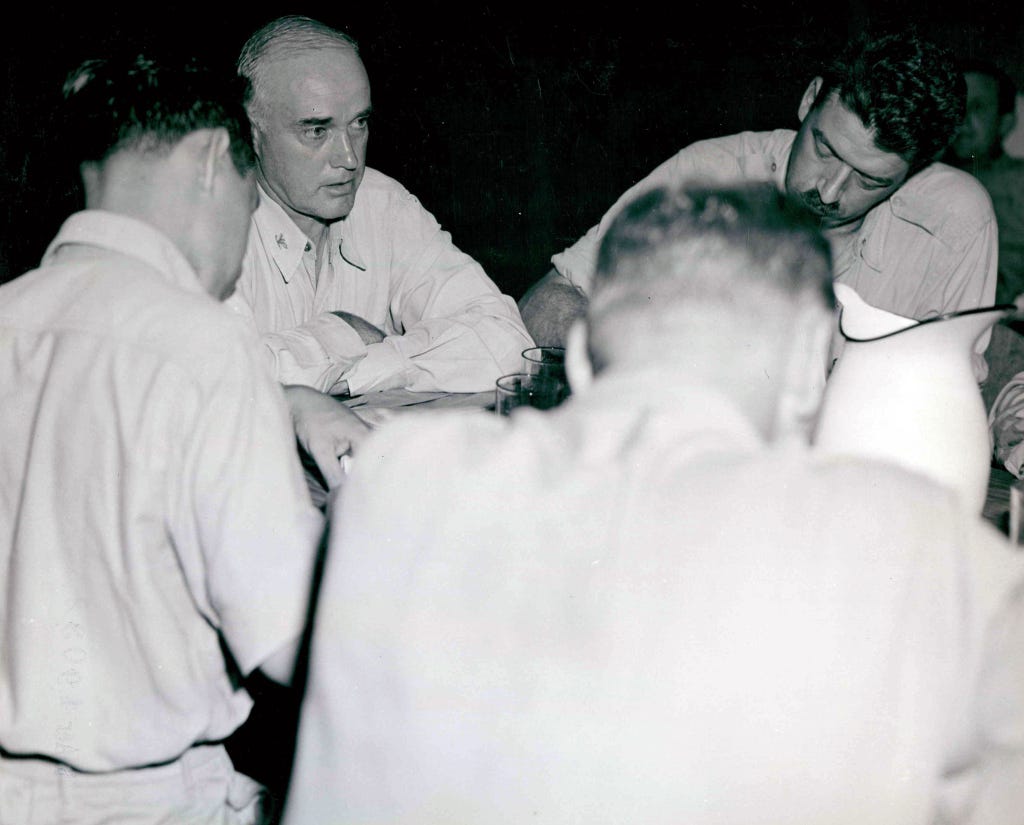

It took two days for the Navy to realize the Indianapolis had gone missing and two more before the first survivors were rescued -- the skipper, Capt. Charles B. McVay III, among them. McVay and the rest of his men eventually were transported to Guam, where the captain and other survivors sat down with reporters to tell the story.

Those accounts were not released for publication by the Navy until 9 p.m. Eastern War Time on August 14, exactly two hours after President Harry Truman had announced the Japanese surrender following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The nearly simultaneous announcement of two massive stories made for quite a juxtaposition in newspaper extra editions:

While some of the casualty numbers released that evening didn't align with what have come to be considered the final counts, the stories filed from correspondents in the Pacific made clear the ghastly nature of the tragedy.

Leo M. Litz of the Indianapolis News turned in some of the most gripping prose in a pair of stories with Peleliu datelines that began on the front page of the August 15 edition. As Litz would describe in his lead story, he caught a 900-mile flight from Guam to Peleliu after hearing of the disaster and arrived only hours after the initial survivors had arrived.

His Page 1 sidebar dateline began:

Stories of indescribable horror, of being tortured by hallucinations that drove men to madness and to death, were told by a small band of survivors from the ill-fated cruiser, U.S.S. Indianapolis, who drifted aimlessly in the Pacific fo four days hoping and praying for rescue.

Now recovering from an ordeal they can scarcely comprehend, men told of their constant struggle against temptation to drink salt water, of frightening experiences with sharks that followed them, of seeing plane after plane fly overhead while they waved frantically and set off signals to attract attention, of being burned painfully by the equatorial sun by day and chilled by night. Mass hallucinations of a nearby tropical island, with plentitude of cold water, drove many to a vain search in which they perished.

After telling the stories of three individual sailors with Indianapolis ties, Litz gives considerable space to recounting the experiences of the Indy's senior medical officer, Lt. Cmdr. Lewis L. Haynes.

Unmindful of the hardship involved, Dr. Haynes swam from group to group, cautioned them against drinking sea water, gave other instructions and boosted morale for an ultimate rescue. At the same time he tried to administer what first aid he could, without supplies, to the burned and wounded. He was clad only in the bottom of half of his pajamas, but he took this off and tore it into strips to dress wounds. He had men lock arms and tried to keep them together.

Litz notes that Haynes did all this despite suffering serious burns in the explosions. Then we hear from Haynes himself:

"These mass hallucinations started on the third day," Dr. Haynes said. "One man told of swimming to an island only two miles away where he was given so much cold tomato juice he was sick at his stomach. Obviously, he had drunk sea water. Yet men listened intently to his fantastic story of a partly submerged island with rooms to rent and started to swim toward it. in large groups despite all efforts to dissuade them. Some came back and said there was no such island, while fully 50 per cent returned with the same story. They said it was a secret island, talked about it in whispers, all planned to go back next day.

"Our last night in the water was the worst of all. Men screaming, fighting, clawing at their faces and bodies. I witnessed several cases of deliberate drowning -- where one man would drown another by holding him under water. Once I was shoved under water by a man who said, 'I'm going to kill you.' I managed to get away. The group was out of control, with many men demented because they had drunk sea water."

Aside from the human tragedy, one other wrinkle made the story even more extraordinary. Litz reported in his prewritten main story that he expected release of the official report "to reveal that the Indianapolis carried the atomic bombs to the Pacific."

Many, many survivors told me the ship carried "special cargo" on the hangar deck that was guarded day and night by Marines who had explicit orders not to permit anyone near it. Departing from Mare Island, San Francisco, Cal., July 16, the Indianapolis broke all speed records for surface craft on the trip to Pearl Harbor and thence to the Marianas, arriving at the latter destination July 26. ...

None of us knew about the atomic bomb at the time I talked with survivors of the Indianapolis here but when the announcement came through a few days later all were ready to believe this had been the "special cargo" they had carried.

The Navy press release the evening of August 14 did indeed acknowledge that the Indianapolis had carried "essential atomic bomb material" to the Pacific before the ship's demise. "Thus, the last mission of this gallant cruiser was to bring to our Pacific bases, which are within bombing range of Japan, materials for atomic bomb attacks on the enemy."

The essential material in question was uranium, along with other components of the "Little Boy" bomb that would devastate Hiroshima on August 6. The Navy's initial emphasis on that critical final mission perhaps served as an effort to temper the questions that already had arisen -- and would continue to echo for decades -- about the hundreds of sailors left to drift for days before any rescue efforts got under way.

Capt. McVay and 36 others were rescued by the USS Ringside on August 3, and he immediately sent a message to Adm. Chester W. Nimitz's headquarters with the basic information about the sinking. It was essentially the message he had ordered sent as the ship was going down, as he would describe to the correspondents on Guam.

McVay told the story "in a calm, undramatic voice," reported Morrie Landsberg of the Associated Press:

Clad in his pajama top, McVay ran to the chart house and told the navigator, Cmdr. John Hopkins Janney of Baltimore, Md. -- now listed as missing: "For God's sake make certain contact reports got out. Say we have been torpedoed. Our position such and such. We are sinking rapidly and need immediate assistance."

The captain ordered all engines stopped. Radiomen tried in frantic desperation to click out their appeal for help. It was no use. There was no power.

The 46-year-old McVay, an Annapolis graduate and son of a Navy admiral, then spoke of his own experience abandoning ship.

"I looked up, and above my head were the two big port screws. I said, 'This is the end of me; it's bound to hit me.' I felt another wave, heard water swishing, and there was nothing there anymore, and I was still there. Why I wasn't sucked under I don't know.

"Next thing I noticed was a crate of potatoes. I got astride, then came across part of a wooden desk. I saw two life rafts within 20 feet, with nobody aboard. I got one, then secured the other."

Another sailor joined him aboard, and the pair soon picked up two more men, then another five. After that, McVay said, "we didn't hear anyone call for help. We thought we were the only survivors."

Landsberg's AP story said the Navy "explained no effort had been made to locate the cruiser until she was 54 hours overdue because warships often are diverted secretly by high authority, or by their own captains; or they may be under radio silence for several days if pursuing an enemy submarine or surface ship."

The rescue delay also was noted prominently by Litz, who wrote: "It was announced this matter would receive attention of a naval board of inquiry."

Rather than focusing on why it took more than 100 hours to fish survivors out of shark-infested waters, the subsequent inquiry delved into McVay's actions. Despite Nimitz's objections, the Navy court-martialed McVay for failing to issue an abandon ship order in a timely fashion and for following a straight course rather than zigzagging to deter potential enemy attackers.

After a 12-day trial, McVay was convicted of the latter charge -- he had acknowledged in his first message to Nimitz's headquarters after being rescued that he had not been zigzagging -- even though the skipper of the I-58, Cmdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto, testified at the hearing that such evasive maneuvers would not have affected the outcome.

Accounts of the court martial's final day reported that the judge advocate leading the prosecution, Capt. Thomas J. Ryan Jr., told McVay "I'm sorry" after arguments concluded. McVay is said to have replied, "It's for the good of the service, whatever the findings."

Gracious as McVay may have been in public, plenty of observers objected to the entire proceeding. Syndicated columnist Ray Tucker led a late-December column that appeared in dozens of newspapers with a screed at the Navy's lack of accountability:

The McVay court-martial procedure was deliberately rigged by the Navy prosecutors at Washington so as to conceal the amazing fact that the naval forces have no orders, no system and no prearranged plan for sending out destroyers or airplane rescue squads for vessels which do not arrive in port on scheduled time. There is no provision in the Navy manual for taking emergency action to search for and salvage an overdue warship and her crew.

To the astonishment of naval personnel, members of Congress and newspapermen covering the trial, that vital question was not raised by the prosecution or the defense. It was not brought up formally, although it was present in every observer's mind, because the indictment had been drawn so narrowly that the naval judges could and would have ruled it out as immaterial, irrelevant and impertinent. ...

But the human loss from the torpedoing of the Indianapolis was not McVay's fault or doing. According to all testimony, more than 800 American sailors perished because the top commanders at Leyte or the Philippines, or both, did not dispatch ships and planes over its plotted course when the cruiser did not reach Leyte at the appointed hour.

The Navy officially announced McVay's conviction on February 23, 1946, but said at the same time that he would incur no penalty due to other factors involved in the tragedy. The lack of a timely rescue operation was chief among them, and multiple officers received letters of reprimand for those shortcomings.

McVay remained in the Navy until retiring in 1949, but he never got over the loss of his ship. On November 6, 1968, he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at age 70.

Further research in the 1990s continued to call into question the case against McVay, and in 2000, Congress inserted language into the 2001 National Defense Authorization Act addressing various issues with the court martial and conveying the sense of Congress that "McVay's military record should now reflect that he is exonerated for the loss of the U.S.S. Indianapolis and so many of her crew."