Sinking of the USS Tang: 'Like the world coming to an end'

The news went public on Feb. 5, 1945, when the Navy announced that the USS Tang was presumed lost after failing to return from a war patrol.

The Tang and her decorated skipper, Cmdr. Richard H. O'Kane, were already known thanks to their heroics at Truk in May 1944, when the sub rescued 22 downed airmen while under Japanese fire. Now they were yet another ship and crew lost during the war -- the 37th U.S. submarine to go down, according to press reports at the time.

Yet there was something uniquely tragic about Tang's demise, though it would take seven more months for the truth to emerge.

Richard Hetherington O'Kane always seemed to find himself in the middle of the action on the seas. The youngest son of a University of New Hampshire entomologist and a 1934 Naval Academy graduate, O'Kane began his naval career on surface ships before transitioning to the submarine Argonaut in 1938.

Argonaut, which specialized in minelaying, was at sea near Midway on Dec. 7, 1941, and a U.S. plane tried to bomb her the following day. The sub eventually returned to Pearl Harbor in late January 1942 before being sent to Mare Island near San Francisco for an overhaul. A year later, Argonaut was sunk off Rabaul with 102 aboard, but O'Kane had moved on by that point, becoming the executive officer of the USS Wahoo in the spring of 1942.

O'Kane served as XO of the Wahoo for five war patrols, the final three under Lt. Cmdr. Dudley Morton. The Wahoo was credited with sinking nearly 95,000 tons of enemy shipping during those three patrols alone.

The sub returned to Pearl Harbor in late May 1943 and O'Kane got his own command that summer, overseeing the commissioning crew for the Tang. The sub was commissioned Oct. 15, 1943 -- four days after the Wahoo was sunk by a bomb from a Japanese plane, killing Morton and his crew.

Tang embarked on her first war patrol Jan. 22, 1944 and sank the freighter Gyoten Maru about three weeks later in her first attempted attack. That was the first of 24 Japanese ships (93,824 tons) the Tang would be credited with sinking during her five war patrols.

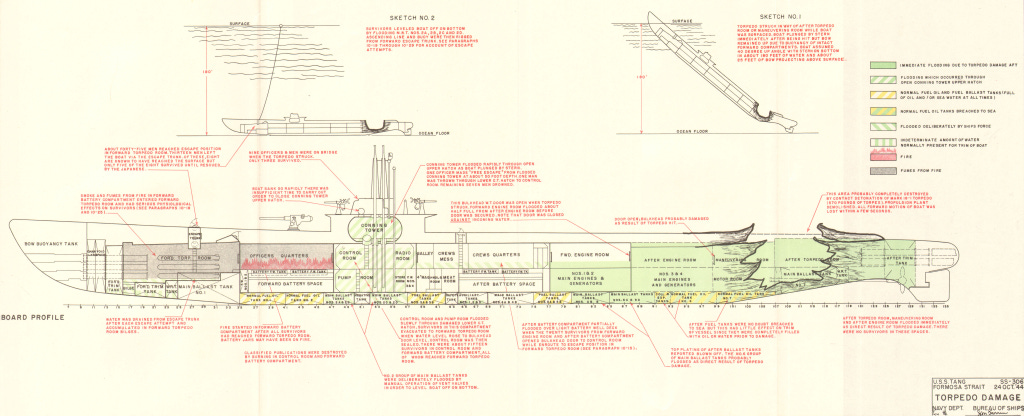

The last would come on her final full day at sea, Oct. 24, 1944. Patrolling alone between Formosa (Taiwan) and the coast of China, Tang launched a night attack on a convoy, firing a series of torpedoes at multiple transports and tankers. O'Kane had two torpedoes remaining to finish off a wounded transport and fired both in succession around 2:30 a.m. on Oct. 25. While the first ran straight, the second curved to the left and came back around on the Tang. Unable to maneuver away, the Tang was hit by her own torpedo and went down in 180 feet of water.

Seventy-eight men were lost, but nine survived, including O'Kane, and they ultimately would tell the story of the Tang's final patrol.

Word of the Tang's true fate began to emerge Aug. 30, 1945, when O'Kane spoke with Associated Press correspondent Hamilton Faron aboard the USS Reeves in Tokyo Bay.

The story said the Tang had been "torpedoed off Formosa last October 25" without getting into further detail. O'Kane described the survivors' ordeal: drifting in life jackets for hours before being picked up by a Japanese destroyer escort and taken to Formosa.

"We were held there and questioned incessantly under constant threat of death for many weeks," O'Kane told Faron. "Then we were transferred to Kyushu and kept in solitary confinement there until last April. Then we were moved to Omori prison camp just over there. It was worse than anything we had seen before."

The following day, O'Kane offered up a bit more detail to Mutual Broadcasting correspondent Jack Mahon in a report later distributed by AP and printed in newspapers nationwide. In this interview, O'Kane described the sub's final attack on the convoy.

"Suddenly, there was a terrible explosion and our stern was blown off," O'Kane said. "I never knew what hit us. It must have been a mine. It was a very heavy blast and it broke the backs of many of my crew."

O'Kane, of course, knew exactly what had hit them, but whether under orders or exercising his own discretion he declined to reveal the full story.

A week later -- notably, after the Sept. 2 ceremony that officially brought the war to an end -- one of the surviving crewmen finally told the tale. Lt. Lawrence Savadkin, who had joined the Tang for the fifth war patrol, spoke to AP correspondent Robert Myers in Guam on his way back home and revealed that the sub had been sunk by her own torpedo.

"We were surface-trailing a convoy in shallow water," Savadkin said. "I was in the conning tower when the torpedo hit. It was like the world coming to an end. I managed to feel my way to an open hatch and was lucky enough to find a huge air bubble which helped me to surface. I must have swum 100 feet to reach the surface."

At 1:30 a.m. on Sept. 7, another survivor, Motor Machinist's Mate 2nd Class Clayton O. Decker, arrived home in Oakland aboard a Navy transport plane. After an emotional reunion with his wife and 4-year-old son, he shared his story with the Oakland Tribune and other outlets.

Decker was one of five men from the forward torpedo room who successfully escaped the Tang after she sank by using the Momsen lung breathing apparatus.

"At 2 a.m. on the 25th we engaged a convoy, sinking seven ships -- we had seven down already," Decker said. "We started back with one torpedo and Captain O'Kane decided to go in and expend the torpedo at a troop transport. It went out forward, but something was wrong and it turned back and hit aft.

"Captain O'Kane and two men on the bridge were thrown into the water. I was forward with 34 other men -- the rest were killed or injured, I guess. The sub went down 180 feet and we laid there about three hours.

"Then I was the first to go through the hatch with the lung. I floated for an hour before the others followed. Nine in all survived from a complement of 74 men. I don't know why more didn't get out."

Decker then described being picked up by the Japanese destroyer, which proved a short-lived salvation.

"It was carrying survivors of the ships we sunk, men with arms and legs blown off, and they really gave it to us," he said. "They kept us tied out in the sun for five days. They put lighted cigaret butts in our ears and nose. They beat us and fed us, during the voyage to the southern end of Formosa, just two hardtack biscuits."

Upon arrival, he said, the men were stripped naked, blindfolded, and led through the streets to a POW camp, where Japanese officers who had studied at American universities conducted the interrogations. Decker told reporters he spent the entire following winter barefoot.

Japanese treatment of the American prisoners also was the focus of O'Kane's first extensive interview confirming the details of Tang's demise. The officer spoke to Johnny Noble of the Oakland Tribune at that city's airport on Oct. 2, shortly after being greeted by four Annapolis classmates upon his return to the U.S.

O'Kane looked "like a skull with living eyes" after months of bare-bones rations in prison camps, Noble wrote. At the time of their talk the officer weighed 138 pounds -- up from "something less than 110" when he was liberated. Wrote Noble:

The best food he got out there after the Tang was sunk was "horse gut soup," and he only got that once a week at the most.

The commander and his crew were sunk more than a year ago last month. Commander O'Kane remembers that event well. He had fired his 24th and last torpedo, completing the end of his mission.

The "fish" made a wild circle and hit the sub in the stern. Jap defense vessels which had been trying to get the Tang had failed, but she got herself there in the remote waters of the China Sea.

On Oct. 6, the Navy confirmed via a press release addressing the fates of six submarines lost during the war that the Tang had been sunk by her own torpedo.

About six months later, now recovered from his ordeal, O'Kane was presented the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman for his actions on the Tang's final patrol. In addition to the nation's highest military honor, O'Kane also finished the war with three Navy Crosses and three Silver Stars, among other decorations.

O'Kane would remain with the Navy through his retirement in 1957, when he exited the service as a rear admiral. He later wrote books about his experiences on the Tang and the Wahoo.

O'Kane died Feb. 16, 1994, two weeks after his 83rd birthday. He is buried in Section 59 at Arlington National Cemetery.