V-1 'buzz bombs' terrorize England

By summer 1944, Londoners were well aware of the rhythms of a German air raid. Though thankfully years removed from the nightly poundings of the Blitz, the capital and the south coast remained forever on alert for sporadic appearances by the Luftwaffe.

When the sirens sounded around 4:30 a.m. on June 13, then, residents knew the drill. But it soon became apparent that something about this early-morning raid wasn't quite right.

A thread of confusion ran through the evening newspapers' reports on the incident later that day. The Coventry Evening Telegraph's account led with news of "an enemy aircraft" being destroyed overnight, with vague references to "activity" in East Anglia, Southeast and Southern England, including London.

The downed aircraft had landed in London's East End (on Grove Road along what is now Mile End Park), and at least 100 nearby houses had been wrecked, with three people reported killed. A civil defense official described the aircraft as "a ball of fire" before it crashed.

The pilot on board must have been blown to atoms as with the exception of one piece of metal fuselage, about six feet long, only very small parts of the 'plane have so far been found. It is believed that a rocket hit the 'plane and set it alight.

The puzzlement is understandable; what plane didn't have a pilot, after all? But the lack of wreckage wasn't the only unusual aspect.

There was something of a mystery about the raid. It was a small force which scattered singly over the south and southeast and the Thames Estuary, apparently mainly on reconnaissance. ...

The force was not sufficiently strong to cause any concern, but the "in and out" flying was puzzling to ground observers, and as a warden in an outer district said, "It seemed they were trying to do a raid in bits and pieces."

It would be a few more days before the press and the public would have the full story, but a new era in airborne terror had arrived over England.

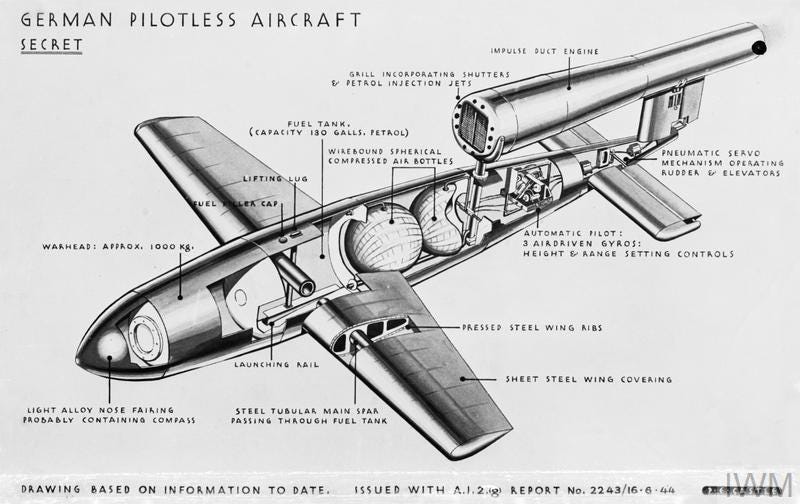

Allied officials had known about Germany's efforts to build what amounted to the first cruise missile since 1943, and had sent bombing missions to target manufacturing and launch sites. Those efforts delayed Hitler's deployment of his "vengeance weapon" but not prevented it.

After what amounted to a successful trial run the morning of the 13th, Germany began a full-fledged air campaign the night of the 15th and into the following morning.

The raid was significant enough to compel Home Secretary Herbert Morrison to address the House of Commons that day. He acknowledged up front that officials had been aware that "pilotless aircraft" were in development and that they were responsible for the damage three days earlier, but sought to reassure the public in terms of the overall threat.

While I thought it right to give the House at the earliest opportunity information about the use of this new weapon by the enemy, available information does not suggest that exaggerated importance need be attached to the development.

All possible steps are of course being taken to frustrated the enemy's attempts to supplement his nuisance raids by means which do not imperil the lives of his pilots. Meanwhile the nation should carry on with its normal business.

As one might imagine, the German take struck quite a different tone. The daily enemy communique cited by British newspapers trumpeted "novel weapons" that had dropped "super heavy explosives" on Greater London.

There will hardly be one German who will not receive this news with the greatest satisfaction. The feelings of hatred and a burning wish of retaliation which dominates the German people have been kindled by our enemies in their terror crimes.

As the onslaught grew in the coming weeks and months, terror would indeed be the watchword for those on the receiving end. Far from the guided missiles of future wars, there was no precision involved in these weapons' targeting process. They were designed for maximum impact on the civilian population, in hopes that an unacceptable level of noncombatant casualties might prompt the British, if not the Americans and Russians, to sue for peace.

Even in the earliest days of their use, though, the British pushed back -- and not just in immediately downplaying the potential impact. Morrison's address to the Commons included a pointed mention that the press had agreed not to report details about specific targets hit by the "flying bombs" so as not to offer up information on their effectiveness.

British officials kept things practical in terms of messaging to the public:

Descriptions of the machines vary slightly in detail, but they agree on these points -- terrific speed, bright lights, flames from exhaust, very straight course.

And of course, there was the sound -- a "noise like an express train" in the words of one eyewitness. A "deafening roar" according to another.

Numerous newspapers on the 16th and 17th featured separate text boxes on their front pages, some in bold print, advising citizens on how to handle this unmanned menace. From a blurb headlined "WHAT TO DO" in the Hull Daily Mail:

When the engine of the pilotless aircraft stops and the light at the end of the machine is seen to go out, it may mean an explosion will soon follow, perhaps in five to 15 seconds. So take refuge from the blast; even though indoors, keep out of the way of blast, and use the most solid protection immediately available.

It quickly became clear to the press that these new weapons would be a regular feature in their coverage going forward. With that in mind, they had to come up with a catchier appellation than the one employed by Morrison and other officials.

"'P-plane', 'bumble bomb', 'robot plane', and 'buzz bomb' are some of the names which have been coined for the news German secret weapon, and they are as descriptive as the severely formal 'pilotless aircraft' of the official communiques," The Northern Whig of Belfast wrote in a June 20 editorial.

By the time that column hit the pages, the last of those alternatives already had begun to take root. The initial dispatch to the U.S. by James F. King of The Associated Press, which appeared in June 17 newspapers, included the term "buzz-bombs".

The other nickname for the weapons was "doodle bugs", which a Newcastle Journal story on June 20 describes as the pilots' term for the enemy aircraft. (The same word had been used to describe remote-controlled German tanks deployed at Anzio.)

Though that term got some use, and continues to, "buzz bomb" would remain the primary shorthand going forward, as evidenced by a stiff-upper-lip editorial in the Daily Mirror on June 21.

We do not underestimate the possibilities of this new type of warfare, or make light of the sufferings of those who are unlucky enough to become its victims. But there is every indication that, while this new form of attack has not yet been mastered, it soon will be. ...

We have the measure of this thing now, and our answer to the Buzz Bomb is Buzz Off!

It wasn't until early July that British and American media began to use the German term for the weapon, V-1, which is generally how we refer to it today.

An International News Service report out of London that appeared in some July 5 papers referenced the official Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter referring to the V-1. A pair of Associated Press stories printed the following day also used the term, which was employed repeatedly by German state radio in response to Winston Churchill's speech to the House of Commons about the ongoing threat:

The German radio declared bombardment of England by "V-1" -- the name the Germans have given to their robot bombs -- had tied down "one whole army" on land, at sea and in the air in efforts to combat it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H95YuznbEYY

Antiaircraft batteries on the south coast and patrolling RAF pilots adjusted quickly and achieved significant success in knocking the buzz bombs from the sky. But they couldn't get them all.

About 2,400 V-1s hit Greater London alone between mid-June 1944 and late March 1945, and though the cumulative toll had no real effect on the larger war, localized impacts could be significant.

Perhaps the most notable hit scored by a V-1 came on June 18, when a buzz bomb plummeted to earth and detonated on the roof of the Guards' Chapel at 11:10 a.m., in the midst of Sunday services. The ensuing blast and collapse of the concrete structure killed 121 and injured 141 more.

Though Londoners obviously became aware of the tragedy immediately, it would be three weeks before officials cleared the press to report on the church's destruction. Accounts of the damage received prominent play in newspapers worldwide beginning July 10, though specific casualty figures were not immediately released.

Though Germany continued to launch V-1s against targets in Britain and Belgium through the spring of 1945, emphasis switched to the larger V-2s beginning in September 1944.

An estimated 18,000 people were killed in V-weapon attacks before Allied troops put all the launch sites out of commission.