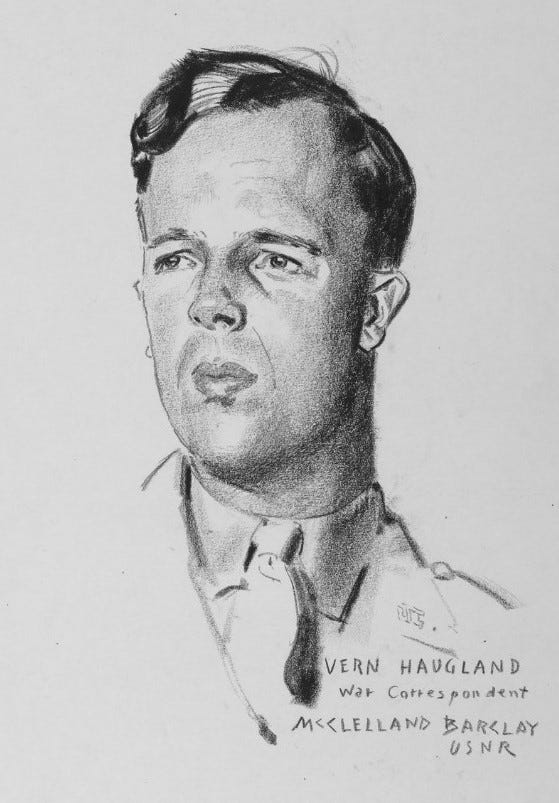

Vern Haugland survived a 43-day jungle ordeal

Folks back in Montana always looked forward to seeing Vern Haugland's byline.

Though he was born in Minnesota on May 27, 1908, Vern was one of their own. He moved to the state at age 5 and began his journalism career in Missoula after finishing college there in 1931. After a stint at the Montana Standard in Butte, he jumped to the Associated Press in 1936, and it was for the AP that he went overseas in January 1942.

Young Vern, the eighth of 11 children of Norwegian immigrants, was quiet but ambitious, a diligent reporter. "He makes friends easily and is relentless in pursuit of a news story," a colleague noted. At 6 foot 3 and 165 pounds, he was often described as lanky, his weight "distributed sparingly" over his frame. "When hunched over his portable typewriter it looked like a toy."

His friends back home kept up with him via the transmissions that came over the newspaper office teletype, pleased to see that "he was getting on as we knew he would," in the words of a September 12, 1942 Standard editorial.

Every man in the office from the back end to the front end and from the top to the bottom was proud to say he knew the fellow who was turning out those stories down in Australia.

Then Vern was gone suddenly. The last word was that he bailed out of a gasolineless airplane over the jungles of New Guinea after receiving last-minute instructions on how to use a parachute. Vern had never made a parachute jump before.

Vern hasn't been seen or heard of since. All of his companions in the airplane except one made their way through the jungle back to Army headquarters. The trip required 20 days for the pilot of the plane. It has been about a month since Vern disappeared.

The boys around the office are hoping and praying he'll show up one day and tell about his experiences in his own easy-flowing newspaper style. They say that if anyone could fight his way out of the jungle, Vern could do it.

The boys were right. Vern did make it back, after 43 days on the run in New Guinea.

It all started with a coin toss.

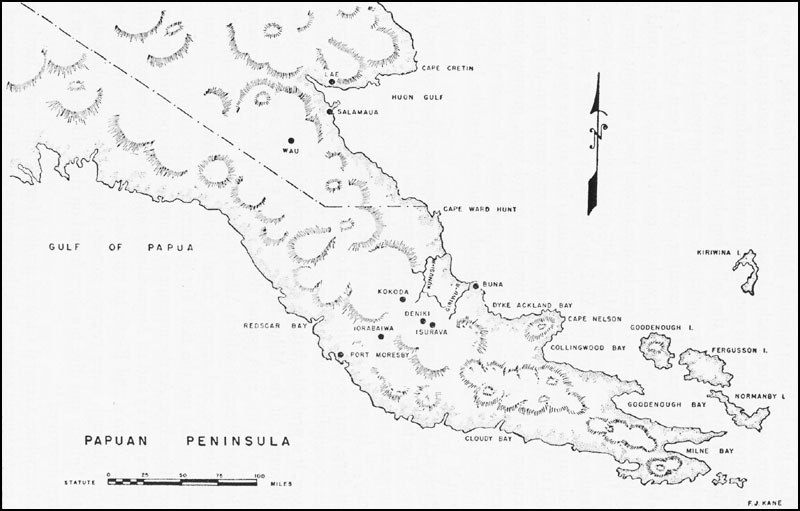

Vern Haugland had written plenty of stories about the war since arriving in Australia in February 1942, but he had yet to see the front lines. He spent four months based in Melbourne, then moved to Townsville on the country's northeast coast in the early summer. Finally, on August 7, correspondents would be allowed to fly to Port Moresby, New Guinea, to begin covering the action on the ground.

Haugland and Geoffrey Hutton, a correspondent for The Argus newspaper in Melbourne, were vying for a seat on a B-26 that would be the first to depart Woodstock Airfield that day: Yankee Clipper, with 1st Lt. Duncan Seffern at the controls. They tossed a coin and Haugland won, relegating Hutton to the second bomber to leave. Midway through the nearly 700-mile flight over the Coral Sea, both planes encountered a heavy storm.

While Hutton's Marauder eventually found its way safely to Port Moresby, Haugland's never materialized. In the midst of the storm, the Yankee Clipper's radio compass and fuel transfer pump failed, leaving Seffern lost and low on gas. The officer, making his first flight as the lead pilot, ordered the crew to bail out, and all eight men aboard exited safely.

"My radioman went out first, then the turret gunner, the tail gunner and then Haugland," Seffern later told reporters. "The navigator told Haugland what to do and then bailed out right after him. This was the first time out for all of us."

The men hit the ground near Mount Suckling in the Owen Stanley Range, a mountainous region about 150 miles from Port Moresby. Seffern and the four enlisted men aboard -- Staff Sergeants Paul Ramsey, George Hickman, Kenneth Gundling and Thomas Riley -- made it to Port Morseby separately between eight and 20 days later. But Haugland, co-pilot 1st Lt. James Michael and navigator 1st Lt. Carroll "Sparky" Casteel didn't materialize.

Though the 34-year-old Haugland had never parachuted from an airplane before, he did make sure to leave the Yankee Clipper with one tool of his trade: a black, paper-bound notebook measuring about 4 inches by 6 inches in which he documented his journey through the jungles of New Guinea until he became too delirious to maintain his diary.

That notebook forms the backbone of what we know about his extraordinary tale of survival, which he later expanded into a book called Letter from New Guinea.

The first entry in Haugland's notebook is from August 7: Bailed out about 6:30 at about 13,000 (feet) nite in chute in rain. Uninjured.

From there, the notations ebb and flow -- brief and basic at first, then facts interwoven with pep talks, moments of despair, and instructions for would-be rescuers.

The following day, he runs into Michael, the co-pilot, who he refers to as "Mike" in the diary. On August 11, Haugland writes: If you find me and not him, send help quickly as he is starving. With food he can make it.

They travel on together until August 16, when they decide splitting up might enable one of them to find help faster and in turn direct rescuers to the other man. On that day, Michael takes a turn writing in the notebook: In case we are separated I'll be up the river in bad need of food please rush to rescue. Lt. James A. Michael, 19th Bomb Sq., 22nd Bomb Gp.

Later that day, Haugland confirms they have indeed split up with this poignant entry:

Mike went up over the hill. I started down the river, saw I couldn't make it and came back to dry my clothes. Will try and follow him tomorrow. Made bed between rock and log. Hope no rain. We may go faster alone. I hope so. He's a wonderful boy and deserves to live.

Haugland's words are increasingly desperate. The day after splitting with Michael, he writes: All I can do is lie and wait, wish for a miracle or death. Two days after that he describes lying on rocks, chewing grass and reeds, praying a great deal. Getting so weak. Hardly any hope now. That August 19 entry concludes, Looks like I shall die here soon.

He is worn down by the seemingly never-ending rain, day and night. August 26: Rained early last night, drenching me. Found dirty hole for head under rotten log -- rest exposed. Awful nite ... Awoke a bit delirious for first time. Looks equally bad tonight -- I'm still wet from last nite.

Two entries after that, he acknowledges he isn't completely sure of the date -- I have been semi-delirious ... two or three days -- but he continues with his diary entries. The following evening he has a second wind of sorts as he nears a mountaintop, giving him a commanding view and hope that reorienting himself might allow him to find his way through the jungle. Whatever happens, God has been good to me.

On August 31, he exults in finding sustenance, even if he can't quite identify it: found two pocketsful of fruit looking and tasting like sour plums. Helped a lot, but too sour to eat many at once.

As the calendar turns to September, Haugland enters a valley and begins to encounter animals -- emu and wallabies -- but finding attainable food remains a struggle. On September 6 he writes: Only chance now native come, I guess. Almost nothing edible several days -- very weak. In a later entry that night, though: Answer to prayers -- dozens and dozens of bramble berries. Sleep under great log -- perfectly dry -- good sleep. Mosquitoes not bad.

Haugland describes finding shelters made from branches, apparently built by natives, and repeated unsuccessful efforts to ford rivers. But on September 9 finally some positive developments:

Spent rainy a.m. in hut drying shoes. Where from here? Impossible stick close to river because impassable tall reeds. Will stay close as can otherwise get lost cause can't see where going.

PM -- Thank God! Keeping near reeds, got on to faint animal track. Crossed stream on log at berry place, trail grew plainer, definitely track thru forest. Make more distance so far than for weeks. ... Sun still high. All creeks logged over, no vines, all cleared.

That entry is the last in his notebook.

The Associated Press moved a story on September 16 reporting organized searches for Haugland had been "abandoned," but the piece still struck an optimistic note. An AP photographer, Edward Widdis, had accompanied one search party traveling by boat up a river and noted that "the natives of the area were generally friendly and had rescued many white men lost for months in the mountain jungles."

At some point after his final diary entry, Haugland wandered into a native village. On September 19, missionaries visited the settlement and found Haugland there, delirious. They recruited natives as litter bearers and carried the correspondent through the jungle until they reached the coast at Abau two days later.

Australian troops were stationed there, and Gen. Douglas MacArthur's chief engineer, Brig. Gen. Hugh J. Casey, had arrived at the port a few days earlier to survey the harbor and possible inland routes for troops. Casey was there when Haugland arrived and sent for a small plane to transport the correspondent to Port Moresby. According to a later Associated Press story:

While they waited for the plane, Casey said Haugland talked about God and his mother, interspersed with periods of incoherent rambling in which he apparently thought himself still falling in his parachute. In an effort to soothe him Casey joined him at times when Haugland broke out in incoherent song.

"I don't know what I sang," said Casey, "but it seemed to help."

It took a few more days for Haugland to recover once he arrived at an Army hospital. His AP colleague Dean Schedler was keeping a vigil at the hospital and reported on September 26 that Haugland was in "grave condition" and had not yet recognized him.

Finally, on September 28 -- seven weeks after he won the coin toss to fly to Port Moresby -- he was lucid again. He recognized Lt. Col. Lloyd Lehrbas, a press aide to MacArthur and former AP correspondent.

"Tell my mother I've been real sick, but I'm all right," he told Lehrbas.

The correspondent would later write to his brother that he weighed just 95 pounds when he arrived at the hospital.

Haugland's remarkable story was splashed across front pages around the United States and beyond, and the AP moved a lengthy piece containing day-by-day excerpts from his diary.

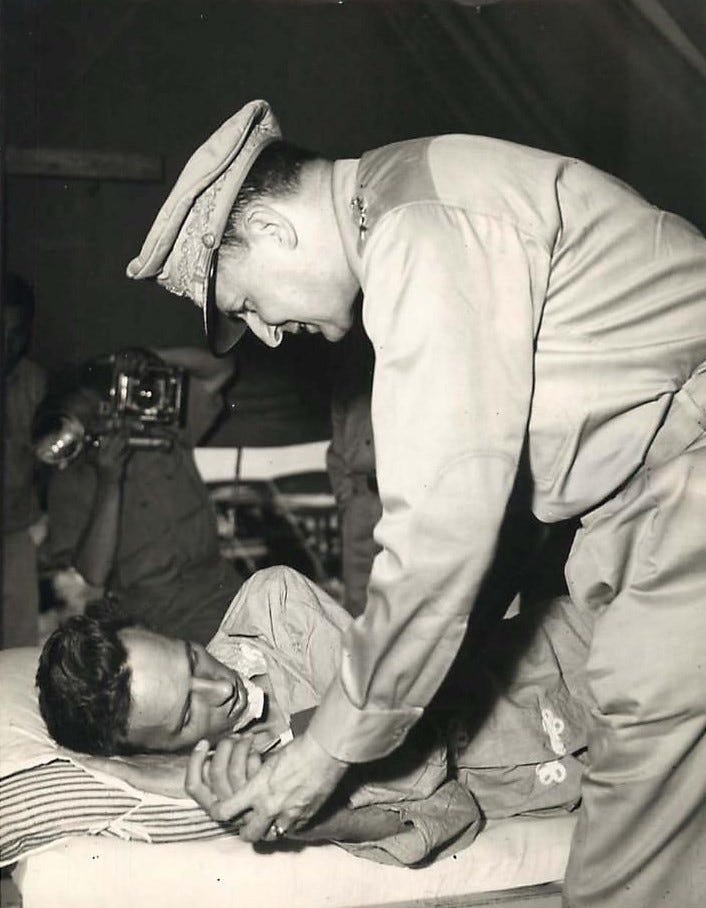

A few days later, as Haugland continued to recuperate, Gen. MacArthur arrived in Port Moresby and immediately asked, "How is that boy Haugland?"

On October 3, MacArthur visited Haugland at the hospital and pinned a Silver Star on the correspondent's Army-issue pajamas -- making him the first civilian to receive the honor.

"I am awarding you the Silver Star as an outward symbol of the devotion and fortitude with which you have done your duty," he said. "I can't tell you how much we have been inspired by your getting back after such tribulations and hardships."

A week after being decorated by MacArthur, Haugland was flown back to Australia on a B-25, with medical personnel aboard to care for him during the flight.

"Physicians said Haugland had shown marked improvement in the last few days and with continued care and rest should recover fully from the privations which nearly cost his life," an AP colleague wrote.

The doctors proved correct. A little over a month later, Haugland was back at work in Australia.

His first byline since his ordeal was a story about Thanksgiving, but it wasn't autobiographical. Haugland simply described how the troops celebrated the uniquely American holiday on foreign shores.

Haugland noted how turkeys had been imported from the United States "since Australia's cranelike turkey is quite a different bird from the American fowl."

Due to tropical storage problems, front-line fighters in New Guinea missed out on turkey, but hospital menus in the Port Moresby area as well as throughout Australia featured the big bird.

Here is the typical menu: Fruit cocktail; roast turkey and ham; sage dressing; cranberry sauce; broiled steak; candied yams; sweet corn; combination salad; celery; olives; nuts; pumpkin pie; apple pie; plum pudding; tea; coffee; milk; cigarettes and cigars.

A few days later, Haugland filed a story on the "Caterpillar Club," airmen who had parachuted out of planes but managed to return safely. Of the more than 100 men who had managed that feat in New Guinea, he noted, were two civilians: "One is an aircraft factory representative. The other is this writer."

The rest of the story described in detail the survival sagas of numerous airmen that undoubtedly resonated a bit more with Haugland after what he had experienced.

That point was hammered home in the new year. Haugland made a proper return to New Guinea on January 9, and the following day watched in horror as a B-26 bound for Australia crashed shortly after takeoff, killing all seven men aboard. The co-pilot of the bomber was Lt. Duncan Seffern, who had been at the controls of Haugland's fateful mission five months earlier.

Haugland continued to cover developments in the Southwest Pacific for another year before finally returning home in the spring of 1944. He arrived in Los Angeles, where his mother and some siblings were living, on April 8 for what was to be an eight-week break after 27 months overseas.

He told reporters he planned to do a bit of skiing, and followed through on that vow -- suffering a broken ankle in the process. That delayed his planned return to the front lines, but he made good use of his time.

On June 3, Haugland married Tesson McMahon of Butte in San Francisco before a small group of family and friends, including the AP's Melbourne bureau chief C. Yates McDaniel. The couple honeymooned in nearby Carmel.

In September, Haugland shipped back out across the Pacific, spending weeks reporting from Pearl Harbor before moving on to follow the Army Air Forces as they worked their way toward Japan. On September 1, 1945, the day before the Japanese signed surrender documents aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Haugland visited a POW camp near Yokohama. His lengthy article recounted numerous stories of torture and degradation suffered by American prisoners.

Haugland returned to the U.S. in 1946 and became the AP's aviation editor five years later. He would maintain that position through his retirement in 1973, with his focus shifting in the late 1950s to coverage of the nascent U.S. space program.

He was on hand for numerous critical moments in the program's history, reporting from Cape Canaveral and Navy recovery vessels in the Pacific alike. He was aboard the USS Iwo Jima in April 1970 when the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission ended with a safe splashdown for astronauts James Lovell, Fred Haise and Jack Swigert.

They were back from moments of extreme danger, from long hours of discomfort, chilled by cabin temperatures in the thirties, tired by the constant battle to keep their battered ship going.

Those trials began Monday night when an oxygen tank in their service module burst, exploding with it hopes for a lunar landing and putting the astronauts' lives in jeopardy.

But their safe return was as if the prayers of a planet were answered.

Along with his coverage of the space program, Haugland also wrote a pair of books about the American Eagle Squadrons that flew with the Royal Air Force from 1940-42.

He was attending an Eagle Squadrons reunion in Reno when he suffered a heart attack and died on September 15, 1984 at the age of 76.

Haugland had two more books in the works at the time of his death, and his wife Tess completed both of them.