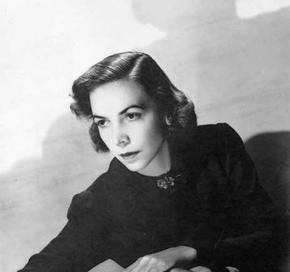

Virginia Cowles, from high society to the front lines

On June 12, 1940, the same day French officials declared Paris to be an open city, Virginia Cowles flew from London to France. Arriving in the capital by train at 4 a.m. on the 13th, she was stunned by what she witnessed.

Thousands of people gathered at the station, begging to be let in only to be told by police that no more trains were leaving Paris. The hotels were closed, telegraph and telephone communication had been shut down, and the hotels were empty of guests.

About three hours after arriving, Cowles tracked down fellow correspondent Walter Kerr of the New York Herald Tribune, who had access to a car and two gallons of gas. With those precious commodities, they toured the city.

Paris was a tragic sight. The sun streamed through the chestnut trees in exactly the same way it does every spring in Paris; but gone were the laughing crowds along the boulevards, the rich smell of tobacco. There were no splashing fountains, no noisy cabs. Only a sweep of lonely, deserted streets. Occasionally we passed cars careening under the wight of mattresses, chairs and bicycles, hurtling down the boulevards on their way out of the city.

Now and then we passed family groups, who were starting out for their long trek on foot. One old woman was wheeling an invalid husband along. When we asked them where they were going they said they didn’t know; they only wanted to get out before “the Boches came.”

The loneliness and quiet of Paris was almost indescribable. Although there were reports that the Germans were only 20 miles away it seemed strange, for there was no sound of gunfire; only an incredible silence. I counted only four cars on the Champs Elysees, and at the Arc de Triomphe, where usually crowds gather, three policemen stood in silent watch over the tomb of the unknown soldier. The eternal flame was still burning.

Though by this point it was just a matter of time and formalities before France’s defeat, Cowles wrote that she saw no resignation on people’s faces. “If ever I saw hatred written across a city it was written on Paris Thursday.”

A brief stop at the American embassy around noon confirmed that Cowles would need some luck to get out of the city before the Germans arrived, and she found some in the form of another correspondent with a car and gasoline, who invited her to drive south with him. In their first 10 hours on the road, they traveled about 40 miles.

A flow of human beings bicycle-riding and trudging along the roads. We passed dozens of overloaded cars that had broken down; we passed people who had run out of gasoline, weeping in despair; old people lying by the roadside, too tired to move any farther.

The villages were tied up for hours by traffic jams, and the flow of people cleaned the shops out of food like a swarm of locusts.

They eventually made it to Tours with help from a motorcycle escort provided by French troops, and Cowles sat down to type out her story for London’s Sunday Times and the North American Newspaper Alliance.

It had been a harrowing few days but that was nothing new for Cowles, already a seasoned war correspondent at age 29.

Virginia Spencer Cowles was born Aug. 24, 1910 in Brattleboro, Vermont, and grew up in high-society Boston. Her father, Edward Spencer Cowles, was a prominent neurologist and psychiatrist, and her mother, Florence, worked as the society editor at the Boston American and the Boston Post.

Virginia got her start in journalism in a similar vein, writing for what were commonly referred to as the women’s pages about society events and fashion, but she soon decided she wanted to expand her horizons.

Cowles set out to travel the world in 1934 and spent more than a year filing stories to Hearst newspapers. She wrote about the life of married women in India, the culture of kidnapping in Harbin, China, and the mood in Rome shortly after Italy invaded Ethiopia. The tagline accompanying her stories in some papers described her as a “noted New York and Boston Social Registerite.”

She headed to Spain in the spring of 1937 to cover the civil war, making acquaintances with the likes of Martha Gellhorn and her future husband Ernest Hemingway. It was Cowles’ first experience in a war zone but she jumped right in, exploring the rubble-strewn streets in high heels.

From that point forward, Cowles seemed determined to remain in the center of the action. Now working primarily for the Sunday Times, she reported from the Sudetenland in the spring of 1938, watched Hitler spark a Nuremberg crowd into a frenzy that fall, and spent weeks reporting from Moscow early in 1939. She flew into Berlin on Aug. 31, 1939, hours before German troops attacked Poland, and in January 1940 went to Finland to cover the ongoing fighting against the Soviets.

She wrote from Helsinki:

It is difficult to convey a picture of what war against a civilian population is like in a country with the temperature 30 degrees below zero. But if you can visualize farm girls stumbling through the snow for uncertain safety in their cellars, if you can see bombs falling on frozen villages, unprotected by a single anti-aircraft gun; men standing helplessly in front of blazing buildings with no apparatus with which to fight fires, and others desperately trying to salvage their belongings from the burning wreckage — if you can picture these things and realize that even children in the remote hamlets wear hastily-made white covers over their coats as camouflage against low-flying Russian machine gunners, you can get some idea what this war is like.

Cowles may have been a “noted New York and Boston Social Registerite” at one point, but now there was no denying her credentials as a war correspondent.

After returning from France in June 1940, she would cover the Battle of Britain and begin work on her first book. The aptly titled Looking for Trouble, a chronicle of her reporting travels, would be released in August 1941 to positive reviews.

Cowles eased off on her peripatetic ways for a while, at least when it came to work. She did visit the now-married Gellhorn and Hemingway in Cuba early in 1942, however.

She also stepped away from journalism for a time, going to work as an assistant to John Winant, the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, but she couldn’t resist the pull.

In January 1943 she took a leave of absence from the embassy and traveled to Tunisia to report on Allied troops fighting there. She did the same in Italy in the spring of 1944 and would travel back to North Africa that summer before returning to France in early fall once the Mediterranean front opened there.

Once the war in Europe ended in May 1945, Cowles enjoyed a happy reunion with a prior acquaintance, RAF Flight Lt. Aidan Crawley, who had spent four years in a German POW camp after being shot down over Libya.

The pair were married July 29 in London, days after Crawley was elected to Parliament. Ambassador Winant gave the bride away.

Cowles continued her work as a correspondent for the Times and other outlets while doing a little creative writing on the side. In June 1946, a play called Love Goes to Press, co-written by Cowles and Gellhorn and based on their experiences as correspondents in Italy, premiered in London.

The following year, Cowles was awarded the Order of the British Empire for her reporting during the war.

In the early 1950s, Cowles embarked on a second career of sorts, publishing a biography of Winston Churchill in 1953. She would spend the next 30 years working primarily as an author, often telling the life stories of the rich and powerful.

She and Crawley were traveling in France in September 1983 when they were involved in an automobile accident that killed Cowles and left her husband seriously injured. She was 73 years old.