A very different Washington Post

Sometime after V-J Day, the War Department produced a list of correspondents who had received official acknowledgement for covering various theaters of the war. The list runs 13 typewritten pages and by my count includes the names of 837 reporters and photographers.

Exactly one of them, Edward T. Folliard, worked for The Washington Post.

It's a mind-boggling notion for someone accustomed to today's media environment, but the Post of that era was decidedly unambitious compared to the present version when it came to global coverage.

The New York Times was the heaviest hitter in terms of staffing on the ground, by one account sending 55 correspondents abroad during the war. But Chicago was the true second city, with the Tribune, Daily News, Sun, Herald-American, and Defender all putting correspondents in the field. Baltimore also had a renowned set of war correspondents filing dispatches to the Sun, Evening Sun, News-Post, and Afro-American. Even the Washington Star had three correspondents on the list.

The Post, however, spent most of the war relying on the wire services to fill up its pages with the news from overseas. It wasn't until January 1945 that the paper sent its own reporter to the front. Folliard, born May 14, 1899, had covered a variety of beats for the Post since 1923, with the exception of two years in the early 1930s at the rival Herald. He had covered the White House for about three years before shipping out to Europe.

Folliard would file 34 stories from the continent, the first of them an account of his transatlantic flight -- still a novel enough concept at the time to rate a story. His last two pieces ran on V-E Day, May 8. One of them detailed a visit to the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich, the site of Hitler's beer hall putsch in 1923.

He had filed a similar piece in March after making his way to Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels' castle in Mönchengladbach. In a story datelined March 12 and printed the following day, Folliard pokes around the remaining treasures of Schloss Rheydt.

Today this reporter examined some of its exquisite china, enough to take care of 55 guests. He also looked over some of the books in the huge library on the second floor.

These included Thomas Carlyle's "Frederick the Great," D. Erskine Muir's "Machiavelli" and John McAuley Palmer's biography of General Von Steuben. There was a whole shelf of books of music and the music masters, including Chopin, Mozart, Schubert, Puccini, Johannes Brahms and Bach.

There was another book, but Goebbels kept this on a cabinet next to his huge four-poster bed. It was a book which included, among others, the names, addresses and telephone numbers of German movie queens.

Right around this time, in mid-March, the Post sent another reporter into the field. Though he didn't appear on the War Department's voluminous list, longtime sports columnist Shirley Povich spent about six weeks in the spring of 1945 covering the Pacific theater.

Already two decades into his astonishing 75-year run at the Post, Povich wrote about Okinawa and Iwo Jima, including an interview with D.C. native Joe Rosenthal discussing the Associated Press photographer's already iconic shot of the flag raising on Mount Suribachi.

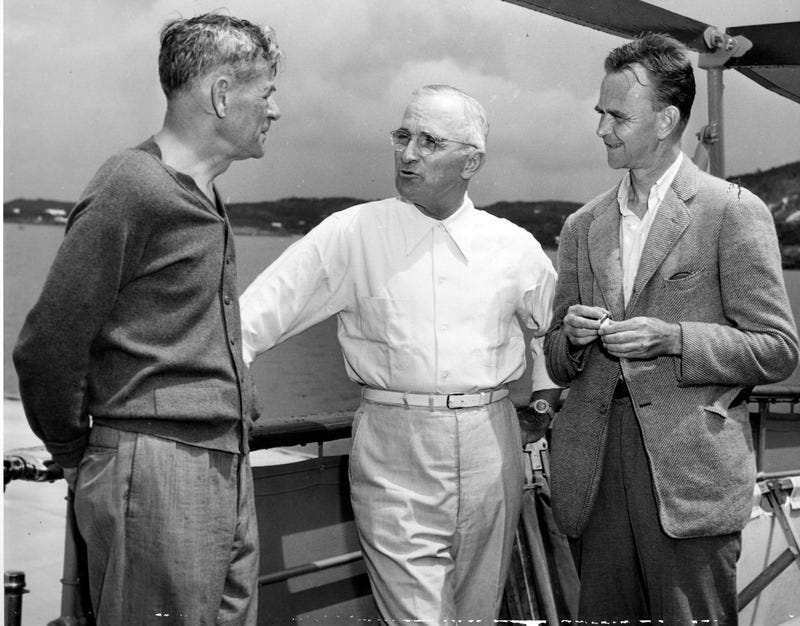

It would take Folliard a bit longer to make it back stateside, but like Povich he immediately transitioned back into his previous role, now covering President Harry Truman on a daily basis instead of Franklin Roosevelt.

Folliard would continue to dabble in a variety of coverage areas for the rest of his career.

He won a Pulitzer in 1947 for a series of stories on a white supremacist group in Georgia and was in the presidential motorcade in Dallas when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963.

Folliard retired in 1966 but continued to write for the Post occasionally through his death in November 1976. Richard Nixon honored him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1970.