One B-25 crew's life-or-death struggle with a rubber raft

Tales of heroism abound in World War II, but they come in many forms. Sometimes, just making it back home was enough.

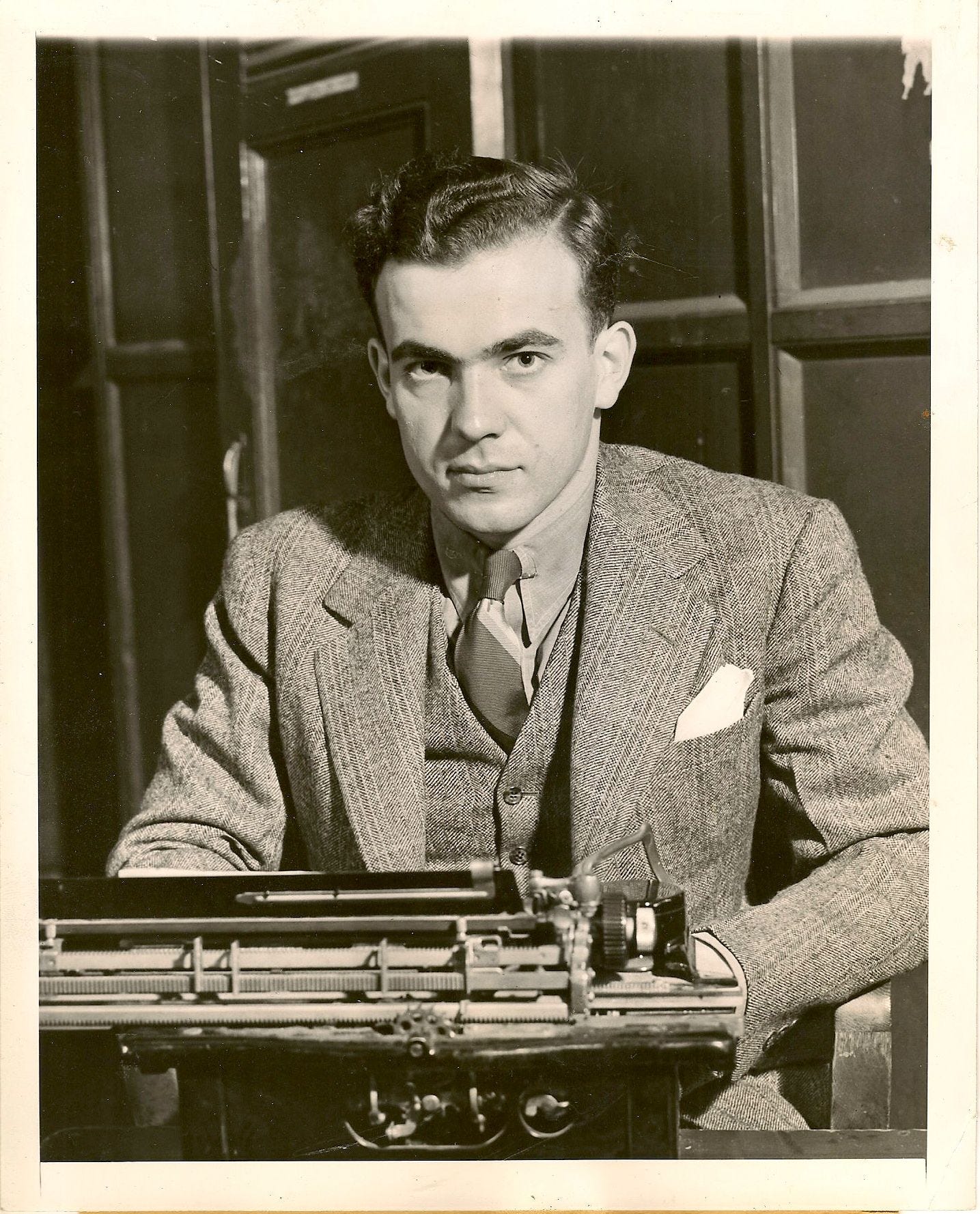

Associated Press correspondent William F. Boni unearthed one of those stories "somewhere in New Guinea," as his dateline put it, telling the tale of a B-25 crew's life-or-death struggle with a rubber raft.

The story, which ran June 30, 1943 in many newspapers, began with the happy ending: a Mitchell bomber piloted by 2nd Lt. Jack W Snyder of Brewster, Ohio, skidding to a stop at an airfield, "a bullet-riddled rubber life raft jammed into the right side of its stabilizer."

Snyder and his crew were on their first mission, a bombing run to an undisclosed target, when the raft strapped to the top of the plane got loose. Boni described the scene:

Driven back through the air by the slipstream it crashed into the stabilizer -- the long horizontal fin set into the tail of the fuselage -- and in the process took along three aerial wires which tangled themselves around the raft as it became wedged into the stabilizer.

The plane immediately was throttled down to below 150 miles an hour only a few hundred feet above a valley. The boys were 200 miles from home.

The raft kept pulling the tail of the plane down, and Snyder and co-pilot Carl M. Denlinger of Dayton, Ohio, were unable to keep the nose down, eventually leading to a stall. They recovered in time by putting their feet on the controls and pushing as hard as they could, Snyder told Boni. This went on for about 30 minutes.

In the meantime, the rest of the crew struggled to find a way to cut the raft loose -- leaning out a window to untangle it manually, trying to hack the wires with a machete -- but no one could reach it. Staff Sgts. Hyman Prosten and John O. Huddleston eventually punched holes in the top turret and shot the raft full of holes with .45s.

At one point, Snyder decided to abandon ship, but T/Sgt. Milton J. Wickhorst had torn his parachute harness in the scramble to throw off the raft. The rest of the crew balked at leaving him behind, so Snyder gave the enlisted man his parachute. But they still wouldn't jump.

"I think we owe our lives to that fact," the co-pilot Denlinger told Boni. "After the first few minutes Jack and I actually had given up mentally on the question of getting home, but still were going through the motions of fighting the ship physically. As far as we were concerned, at one point there was only one question: Should we crash her into a mountain side or spin out?"

They didn't have to make that choice, continuing to fight the bomber until they managed to get her back home, plane and crew intact.

"Anyway," said Snyder, "all our stuff hit the target area -- we almost did, too."

That good fortune didn't last for some of the crew. Snyder, Prosten and Huddleston were on a B-25 that disappeared in January 1944 and was never recovered.