'Blackest' days for war correspondents

Every war correspondent was a volunteer, and each of them knew the dangers of what they were about to experience. That knowledge was reinforced with the occasional news item, recurring periodically since the war began, that another of their own had been killed, wounded or captured.

Nonetheless, a series of tragedies over the course of about a week in August 1944 shook the brotherhood to the core -- "the blackest days of the invasion," as battle-hardened Associated Press correspondent Don Whitehead put it in an August 22 story. Within that stretch, two correspondents had been killed and another gravely wounded, with two more injured and another captured.

"The luck of the war finally turned," Whitehead wrote.

It began August 14, when Gault MacGowan of the New York Sun and William Makin of Britain's Kemsley Newspapers were captured near Chartres after two German armored cars ambushed the jeeps in which they were riding. Makin was seriously wounded, shot in the stomach, while MacGowan was uninjured. Paul Holt of London's Daily Sketch had been riding with them but was able to escape.

Their captors initially told MacGowan that Makin was expected to live after undergoing surgery at a field hospital, but word soon filtered back to Allied lines that his prognosis was grim. (Makin would succumb to his injuries on August 26.)

A little over two months after D-Day, the number of correspondents in the field had grown significantly, with the big prize on the horizon. Everyone wanted to be with the troops that liberated Paris, and correspondents felt increasingly emboldened to be near the action now that the Allies had broken out of Normandy and were driving toward the capital.

On August 17, William Stringer of Reuters and photographer Andrew Lopez of ACME Newspictures were searching for a command post northwest of Chartres when they decided to check on a burned-out jeep by the side of the road.

"We slowed down and then there was a terrible explosion," Lopez told Whitehead. "We hadn't even heard a gun fired. I looked around and saw he was hit. He never knew what hit him."

Stringer was just 27 years old, a native Texan who met his wife, Ann, at the University of Texas. They married in 1941 and began working as foreign correspondents covering South America for the United Press. By the summer of 1944 she was working in UP's New York office and had been stunned to see her husband's byline on a dispatch from the Normandy beachhead shortly after D-Day -- she hadn't heard from him in weeks.

Ann had been scheduled to set sail for London in late August to join Bill in coverage of the war in Europe, but canceled her ticket when the War Department notified her he had been killed.

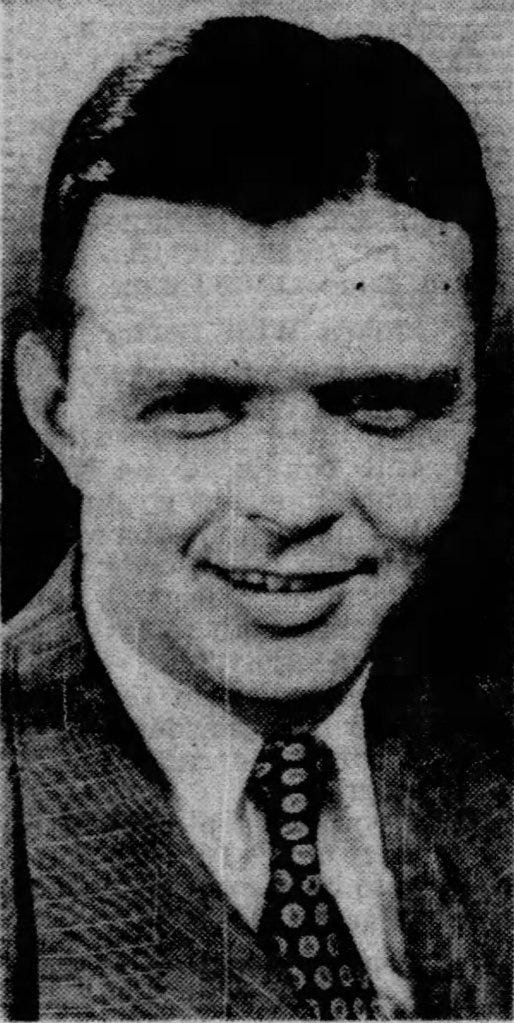

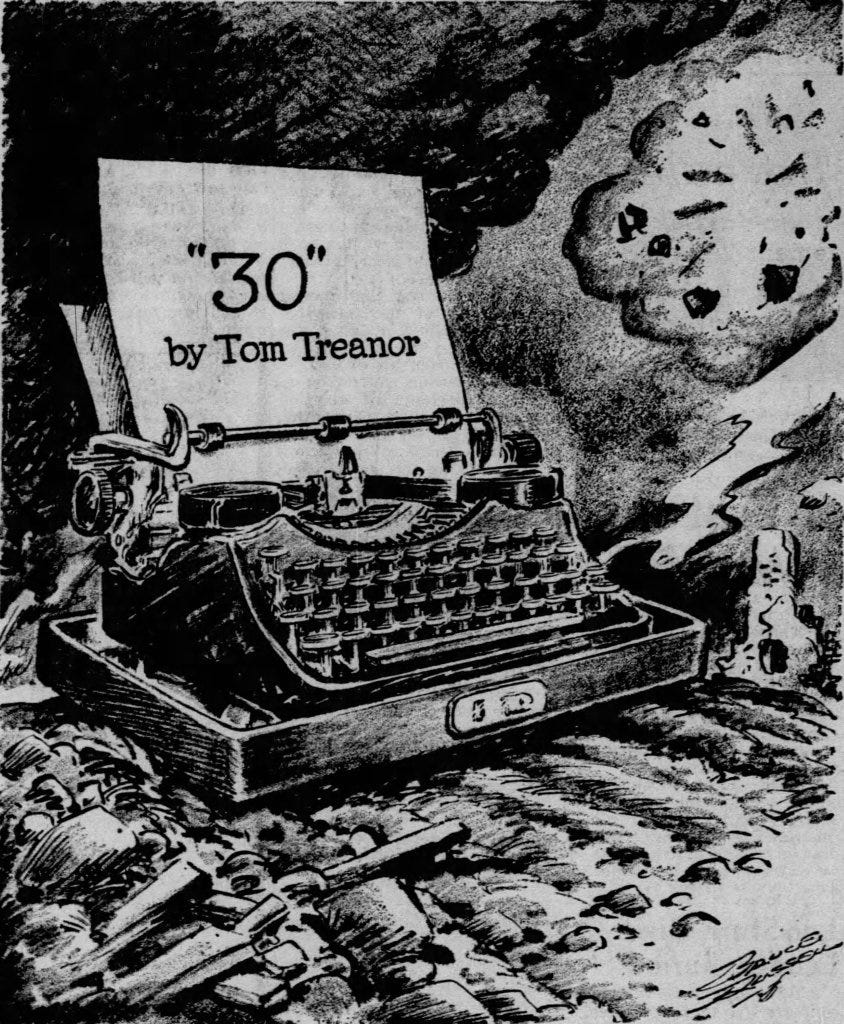

While the youthful Stringer was a relative newcomer to the war correspondent fraternity, Tom Treanor had been in it for the long haul. The Los Angeles Times' star reporter and NBC correspondent had covered the war from North Africa through Sicily, Italy and into Normandy and Brittany.

Known for eschewing the public relations bureaucracy to get as close to the action as he could, he was riding with Charles Shaw of CBS and another correspondent east of Chartres on the evening of August 18 when they decided to pass a column of American tanks ahead of them. As they were moving up the side of the road, a Sherman tank swerved to the left and crushed the jeep, leaving all of the occupants of the smaller vehicle with broken limbs and Treanor with significant internal injuries.

The correspondent was rushed to a field hospital and underwent surgery, taking 10 pints of blood, but died at 4:30 a.m. on August 19. He was 35 years old and the father of three young children.

The Times ran a series of tributes from local luminaries to the reporter, a Los Angeles native who had worked at the paper for 10 years. Earlier in 1944, he had briefly returned home to promote the release of his wartime memoir, One Damn Thing After Another, before returning to Europe in time to cover the D-Day invasion.

His fellow correspondents chimed in as well, with multiple accounts noting that Treanor, still conscious before undergoing surgery, insisted that his colleagues get the name and address of the attending physician, Capt. William Werner, who was from Los Angeles.

An Associated Press story on his death reported that Treanor had called out to a photographer immediately after the accident: "Did you get a picture of me under that tank? This is a hell of a thing to happen to me just before we get to Paris."

That AP story concluded: "Wherever men revere the memory of a reporter who never let danger, hardship or Army regulations stand between him and a good news story, the name of Tom Treanor will be remembered."

The final word ultimately belonged to Ann Stringer. She decided to ship out to London after all, arriving in late fall 1944, and badgered U.S. Army public relations officials into allowing her to go to the front early in 1945. She filed numerous stories to the United Press along the way, filing from the bridge at Remagen and the newly liberated Buchenwald and Dachau camps.

But her signature story came on April 25, when she landed in Torgau, on the Elbe, and became the first correspondent to report on the linkup between U.S. and Russian troops.

Stringer went on to cover the Nuremberg trials and other stories around Europe, before returning to the States. A 1987 New York Times profile devoted its closing line to her enduring connection with her late husband: "We shared every interest," she told the paper.

Ann Stringer died of a heart attack in January 1990. She was 71 years old.